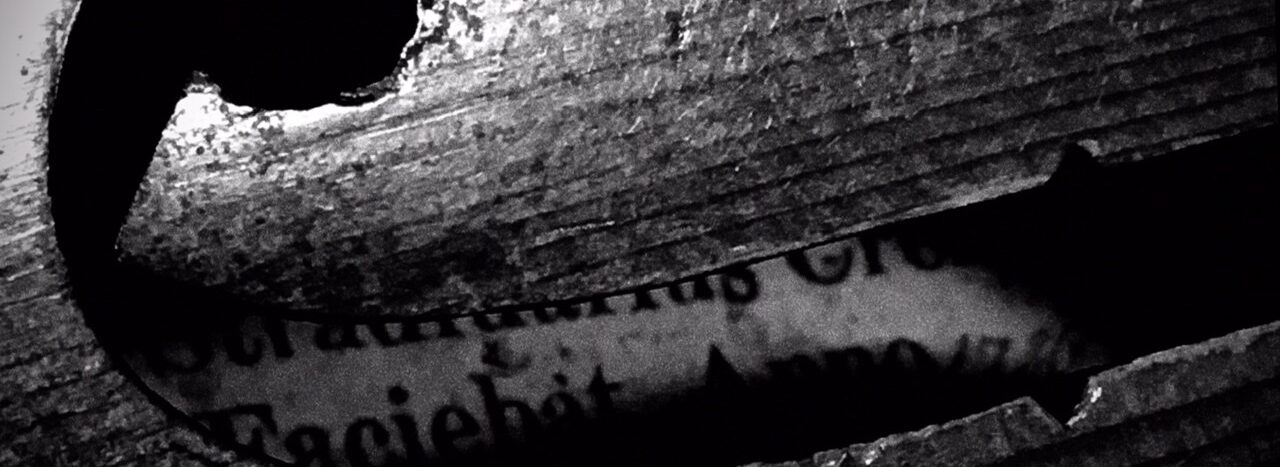

We are all hostages. Start with an image from critic/philosopher John Berger’s 1973 documentary, Ways Of Seeing, which examined the changing construction, consumption and ideologies of art and image. Faceless selves sit behind a suave and sate young man adhered to by two adoring women. This is desire, glamour, prowess. It could be an ad for anything; here it is the power of credit, the pheromone of wealth. It is enticement and also threat. You can be the young man engorged with the latent force of capital, conversely, you could be nameless, faceless, impotent, with no imago at all.

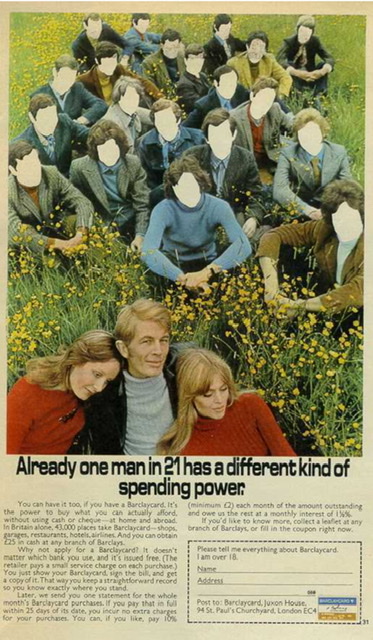

Flip a coin. Here is cult of personality in the fetishised object of desire. The rose and tannin and bergamot, the compelling trace of decay unconsciously activating the basal ganglia. That death stench of ambergris preserved in oils and aromatics. This Is a warning, a threat, an uncompromising invitation. No need to give the year. The design and intent have not changed in a century. Add to it a label; type written on an aged strip of embossed linen paper.

We are captives. This is a ransom note. What it demands is nothing more than complete subservience to the carefully constructed image of the self.

Tear the page. Here is British photographer Richard Avedon’s 1958 portrait of an ageing Gabrielle Chanel. Grown old disgracefully. In that same iconic paint and couture, become a kind of mockery, a clown. The image torn from its prior state of careful cultivation. Become ragged. The locus of sensuality inviting now only that too thick lavender stench. The ambergris rotten. The exposed throat and chin with that wasting and vulnerable aspect of a beached and capsized cetacean. The behemoth picked at by swarming gulls in joysome, childish laughter. One imagines the entire carcass, roped and dragged like Gulliver, craned and submerged, slowly dissolving in the steel vats of some vast industrial process. This is also a ransom note.

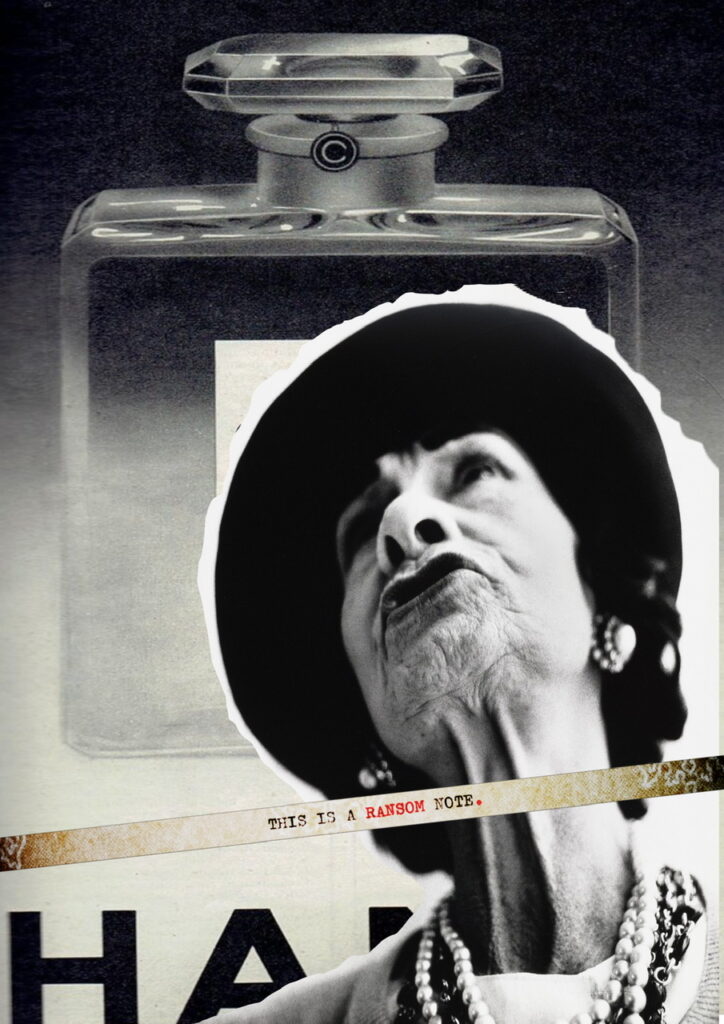

Splashed across the grimed walls and monoxide spewing orifices of urban mass transport systems, leaching euphoric aldehydes from glossy magazine pages, are Barbara Kruger’s slogans. The stratagems of advertising are marshalled to a kind of bland political didacticism, posing as art. What is she selling other than the conventions of a mediocre, bourgeois ideology in the grain and bold of disposable newsprint. Tear it up.

In Barbara Graham’s mugshot, we strike almost the same note; but something more. Here is desperation, and fury, and beauty pared back to a few brute strokes. This Is Barbara Kruger’s ransom note, and obscured by that imprisoning montage, torn from some lost poem, a stray, unwieldy, transformative word; This is Barbara Graham’s love note. “Good people are always so sure they’re right.”

Now, a word from our author – breaking the fourth wall, let me declare; I am quite old. A recent ophthalmograph revealed that I am short-sighted in one eye, long-sighted in the other. Thus, living in the blur not only goes some way to describing my aesthetic, but also my reality. The middle ground is a haze, up close – personal – expect an unrepentant perspicacity; from a far distance, a heightened perspective. I suspect, in this double vision, a deeper aetiology.

Here we focus on our two disparate, concluding images; This Is Barbara Kruger’s Ransom Note, and In The Dawn I Warn Myself Against The Dangerous Moonlight. The first is, although layered in its didacticism, eminently knowable. We know the exact time, the exact place; the stark inhumane light and subjectifying reality of a police station; the woman’s story – one of brutality given and returned – plain as the bruises on her face.

The other is eminently unknowable; we are told it is dawn, but is it? There is an alien, artificial quality to the sourceless light. The streetscape – silhouetted trees and Victorian water-tower – in sharp relief, could be almost anywhere. Montage, as Druckery says, is either discursive or dialectical; “The dialectical mission is to fuse fragments as concentrated form; the discursive one is to create fissures or interruptions in the established order.” (p.4) Where one unmakes the world, the other remakes it.

A hazy figure, by its garb, out of time, follows, but is divorced from itself. In the doppelgänger, Freud finds the returned imago of the self, once a reassurance of immortality, also “becomes the ghastly harbinger of death” (1919, p.9), evoking a sense of terror, of the uncanny.

The uncanny is evoked when the familiar is returned to us not only in unfamiliar guise, but outside of our ability to easily fit what we see into a sensible and apprehensible way of knowing (1919, p.16).

There is indeed something, uncanny, unknowable, something that unhomes us, that unmakes our understanding, between the burgeoning pre-dawn and the disoriented and disorientating figure. Here we have the familiarity and displacement of the dream. Between these two, the crumpled, ransomed woman, a narrative of hard facts and unrelenting sensation, and the unknowable figure haunted by an ungraspable, ersatz satellite, between the known and the unknown, is the eye, the gaze of the viewer.

After John Berger, we may say in one we have the prurience of the real – she “is not naked as she is. She is naked as the spectator sees her.” (1973, p.50) Defiantly returning our gaze, there is nothing like bruises to reveal her in her nakedness – the nakedness the viewer demands. This is an image that serves. It serves the state, the police, it serves systems of measurement, of commerce, of categorisation, of judgement, of plain, calculating reason. The other does not serve. In a kind of unprivileged object oriented ontology, the tower, bold as Tarot, the satellite, both star and moon and emblem, disrupt readily apprehensible meaning. In stark relief, have their own nature, their own irreducible agency, distinct from but intertwined in the fragility of orbit; it is the human, the anthropocentric, that, although originating both, nevertheless is out of place.

The first image, despite fraught sensation and ineluctable consequence (or indeed, because of them), draws us in to an all too human narrative. The second projects a frozen eternity, as philosopher Graham Harman said, such objects define “unified realities – physical or otherwise – that can not be reduced either downwards to their pieces or upwards to their effects.” (2014)

We, with the figure, are trapped in its dream.

Can we really divorce realities from the systems that have made them – think Frankenstein’s creature escaping into the tabula rasa of the arctic wilderness, where the dreams of objects are haunted by the ephemerality of their human originators – or is this just an anthropomorphised projection, a quirk of the ontologies and systems by which we assume, via a self-satisfied and overweening knowledge, a cold and haughty distance?

In pursuit of the self, unless we adhere to those carefully constructed and continuously blazoned parameters propounded by unconscious ideologues and the images and ideas by which we are all held hostage, there is now only a shifting blur of doubt. There are no good people. We are prisoners. With a fishhook mouth, and impotent hands, crumple this up and pin it to the sky. There is no room left for any other conclusion.

References

Berger, J (1973) Ways of seeing, BBC and Penguin Books, London

Druckery, T (1994) From Dada to digital; montage in the twentieth century, Aperture, Aperture Foundation, New York, https://archive.aperture.org/article/1994/3/3/from- dada-to-digital

Freud, S (1919) The uncanny, Strachey, A, trans. https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf

Harman, G (2014) Art without relations, ArtReview, https://artreview.com/September-2014-graham- harman-relations/