In Beyond The Pleasure Principle Sigmund Freud describes how he observed his young grandson playing a game in which he would throw his toys, or any little thing, away into the corner of the room or under the bed, uttering a forlorn or angry cry as he did so, which Freud took to mean “gone” or “away” (fort in the original German).

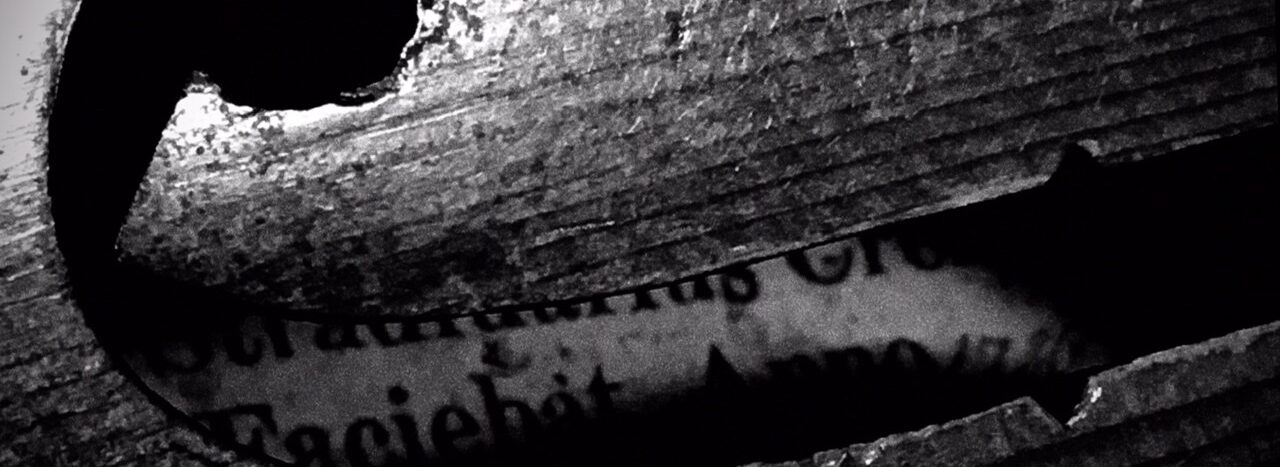

Later the toddler, Ernst was observed playing a more developed version of the game; he would repeatedly throw a wooden reel with string attached into his cot, crying his small expressions of command or consternation when the reel disappeared from sight. Then with some delight, and another rudimentary cry, (this time an approximation of Da! – meaning “There!” or “Here!”), he would reel it in again.

The game was played as a response to the absence of the child’s mother. To Freud the Fort/Da! game demonstrates how pleasure and pain are inextricably linked in the psyche, how early we learn to take such measures, to make such gestures, to gain a semblance of control, of understanding, from loss, from absence and need, of how one person or object can stand as a substitute for someone else, and indeed through symbolic gestures, how we will repeatedly recall or re-enact a painful experience by such exertion in order to engender a pleasurable one.

The French philosopher and linguist Jacques Lacan, analysing Freud’s Fort/Da! game, saw not only an entry into the symbolic, but the destruction of the real. The grief experienced by the child at the mother’s absence is denuded of its power, of its effects, by turning her into a symbol, by controlling her, by destroying her, through the interplay of presence and absence; as the object of need, she can never quite return to that pre-linguistic, pre-symbolic, ultimate real, that according to Lacan is destroyed by word and symbol.

While through this performance of an act, of a spell, rather like the primitive mimesis of sympathetic magic, though pain is temporarily allayed (or perhaps, alloyed), we can only conclude that the pleasure of the presence of the object of desire, now no longer quite as real, is also lessened. So the child cries, clutching at his mother’s skirts, even when she returns.

In this tantrum, in this petulance, we not only begin to see the necessary first becomings of the individuated self, but also the first formations of poetry. In the rhythmic cries, in the conflict of desires, in the play and transformation, in the creation and control of the symbolic, in the outpouring demand and the inpouring need, in utterances that embody the contradictions of need and want, in the way we deform the real to create objects of amusement, of rancour and delight.

Philosophy and psychoanalysis, at their best, are largely works of language and the imagination. A Fort/Da! game in search of the meaning of presence and absence, of pleasure and pain, of being and non-being, of nonsense and significance, of desire and despair, rather like the continual inquiry of the poetic.

Of course philosophers and psychologists find prodigies and marvels in what seems readily apparent to poets; that in a realm where symbols are filtered through the idiosyncrasies and significances of the self, we enter an arena of transformation and interchangeability.

In children’s poetry, whether in the fabrications of the young, the boasts and taunts of the playground, or in the strange and divinational chants that count who is out and who is in, there is a ruthless kind of measure. In the raucous expressions of amusing rhymes and nonsense, or in the raw and dreamlike anxieties of nursery rhymes and folklore, though we may think they are composed by adults, by the search for essence, the act of simplification and reverie itself, we are reaching back into the primal symbols and desires of that first savage and formative game.

A cotton reel easily becomes an absent mother, and with a string, an obedient puppet. A toy becomes the self, the self the dream. In broken boughs and broken crowns we have other primal metaphors. It is easy to forget that the playground has its own defiance, born of a primordial Darwinian politics, until we remember, perhaps, that;

Jingle bells, Batman smells, Robin ran away, (Traditional; – circa 1967).

It also has ways of emphasizing that acts of defiance must have consequences;

My momma told me, If I was goodee, She would give me, A rubber dolly, But Sally told her, I kissed a soldier, And now she won’t give me, A rubber dolly, (Traditional; – circa 1930).

Childhood also has its essential tragedy;

Ladybird Ladybird fly away home, Your house is on fire, your children alone, All but one, and that’s little John, And he lies under the grindle stone, (Traditional; – circa 1770).

Between the doggerel of mockery and obedience, beyond the charming melancholy of untrammeled tragedy, we can perhaps find another way, beyond authority or moral didacticism, where tomfoolery and beauty meet, in a spell of wild divination, and see again as children;

Intery mintery cuttery corn, Brambly briar and brambly thorn, Wire and briar and barrel and lock, Three fat geese in a flock, One flew east and one few west, And one flew over the cuckoo’s nest. (Traditional; – circa 1888). Intrigued? For further reading I highly recommend; Cinderella Dressed In Yella; The first attempt at a definitive study of Australian children’s play rhymes. 1969, Heinemann Educational, Melbourne. Edited and selected by Ian Turner, June Factor and Wendy Lowenstein

Or, The Book of Bird & Bear, 2019, Maximum Felix Media, Korumburra, which features a selection of my poems inspired by the rhymes, fantasies, nonsense and folklore of childhood, available now from Amazon in the link below, and the usual other online venues.

***